Eye Anatomy

To understand glaucoma, it is important to have an idea of how the eye works and the different parts of the eye.

Understand the Eye to Understand Glaucoma

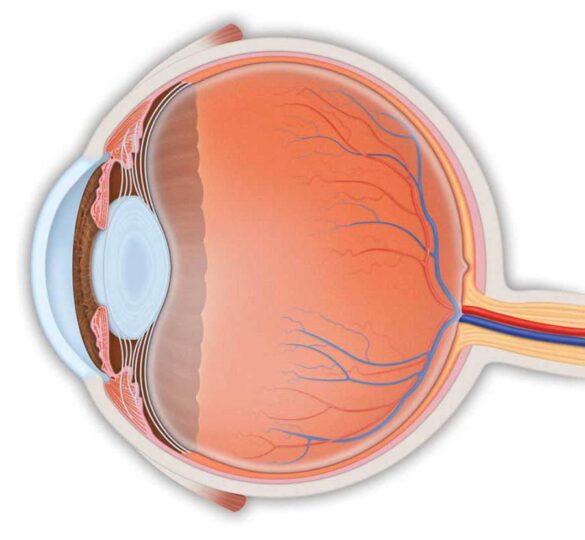

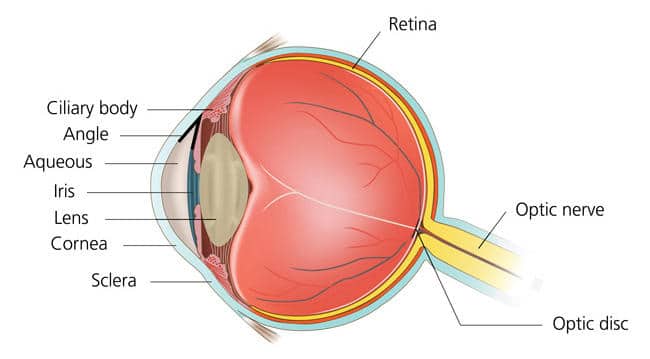

Covering most of the outside of the eye is a tough white layer called the sclera. A clear thin layer called the conjunctiva covers the sclera. At the very front of the eye is a clear surface, like a window, called the cornea that protects the pupil and the iris behind that window.

The iris, a muscle, is the colored part of the eye that contracts and expands to let light into the eye. At the center of the iris is a hole (covered by the clear cornea) called the pupil, where light enters the eye.

The lens inside our eye focuses this light onto the back of the eye, which is called the retina. The retina converts the light images into electrical signals, and the retina’s nerve cells and fibers carry these signals to the brain through the optic nerve. The optic disc is the area on the retina where all the nerve fibers come together to become the optic nerve as it leaves the eye to connect to the brain.

Healthy Eye Drainage

The front part of the eye is filled with a clear fluid (called aqueous humor) made by the ciliary body. The fluid flows out through the pupil. It then reaches the eye’s drainage system, including the trabecular meshwork and a network of canals.

The inner pressure of the eye (intraocular pressure or “IOP”) depends on the balance between how much fluid is made and how much drains out of the eye. If your eye’s fluid system is working properly, then the right amount of fluid will be produced. Likewise, if your eye’s drainage system is working properly, then fluid can drain freely out to prevent pressure buildup. Proper drainage helps keep eye pressure at a normal level and is an active, continuous process that is needed for the health of the eye.

How Glaucoma Affects the Eye

You have millions of nerve fibers that run from your retina to form the optic nerve. These fibers meet at the optic disc. In most types of glaucoma, the eye’s drainage system becomes clogged so the intraocular fluid cannot drain. As the fluid builds up, it causes pressure to build inside the eye, which can damage these sensitive nerve fibers and result in vision loss. As the fibers are damaged and lost, the optic disc begins to hollow and develops a cupped shape. Doctors can identify this cupping shape in their examinations.

Intraocular Pressure

A normal intraocular pressure (IOP) ranges between 12 and 22 mmHg (“millimeters of mercury,” a measurement of pressure.) If the pressure remains too high for too long, the extra pressure on the sensitive optic disc can lead to permanent vision loss.

Although high IOP is clearly a risk factor for glaucoma, we know that other factors also are involved because people with IOP in the normal range can experience vision loss from glaucoma. Identifying these other factors is a focus of current research.

Vision Loss in Glaucoma

Glaucoma usually occurs in both eyes, but increased eye pressure tends to happen in one eye first. This damage may cause gradual visual changes and loss of sight over many years. Often, peripheral (side) vision is affected first, so the change in your vision may be small enough that you may not notice it. With time, your central vision may also be affected. Sight lost from glaucoma cannot be restored. However, early detection and treatment can prevent vision loss and maintain remaining vision.

Optic Nerve Anatomy Video

The information in this article is derived from Glaucoma Research Foundation’s booklet, “Understanding and Living with Glaucoma.” Order or download your free copy.